Transformative governance does not always arrive draped in steel and glass. It does not depend on megaprojects slicing through skylines or ceremonial inaugurations broadcast in prime time. Often, it begins at street level — at a crowded bus terminus in North Chennai, along a market artery in T. Nagar, beside a suburban railway platform in Tambaram. In Tamil Nadu’s capital, a quiet but profound reordering of civic priorities is underway. The expansion of Chennai’s Public Convenience Toilet network is not merely a sanitation upgrade; it is a declaration of administrative seriousness — and a benchmark for the rest of India.

At its most immediate layer, sanitation is public health policy in concrete form. In dense urban corridors, disease transmission rarely explodes dramatically; it accumulates invisibly. Unmanaged wastewater, contaminated touchpoints, open urination in high-footfall zones, and deteriorating facilities generate a persistent microbial backdrop. Chennai’s insistence on clean, consistently serviced public toilets interrupts that chain of exposure. Each functioning unit operates as a decentralised health safeguard embedded within the city’s urban grid.

The dividends of such interventions are incremental but compounding. In a metropolis of millions, marginal reductions in infection rates translate into measurable declines in healthcare burden. Fewer gastrointestinal illnesses mean fewer lost workdays. Reduced exposure lowers household medical spending. Pressure on primary care facilities eases. In this calculus, sanitation precedes treatment. It is infrastructure designed to prevent the need for additional infrastructure.

For women across Chennai, the implications extend far beyond hygiene. Access to dependable sanitation reshapes the geography of daily life. Without reliable facilities, mobility becomes constrained — work hours shortened, commutes negotiated against discomfort, participation in informal commerce weighed against risk. Predictable access alters that equation. It restores autonomy over time and movement. It transforms public space from a zone of endurance into a domain of participation. The social and economic reverberations exceed the footprint of any single facility.

Equally consequential is the recalibration of labour dignity. Historically, public sanitation in many Indian cities has relied on precarious, informal arrangements. Workers operated in invisibility, with limited protections and erratic compensation. Chennai’s performance-monitored model restructures that dynamic. Roles are formalised. Payments are stabilised. Service standards are codified. Cleanliness becomes an enforceable obligation rather than an afterthought. The dignity embedded in this system extends not only to users but to the workforce entrusted with its upkeep.

As these micro-transformations accumulate, their impact becomes sensory. Bus stands no longer signal neglect. Market peripheries shed odour and decay. The visual language of disorder recedes. Urban governance is experienced through the everyday: through surfaces, smells, and signals of maintenance. When the most basic civic facilities function reliably, the city projects administrative control.

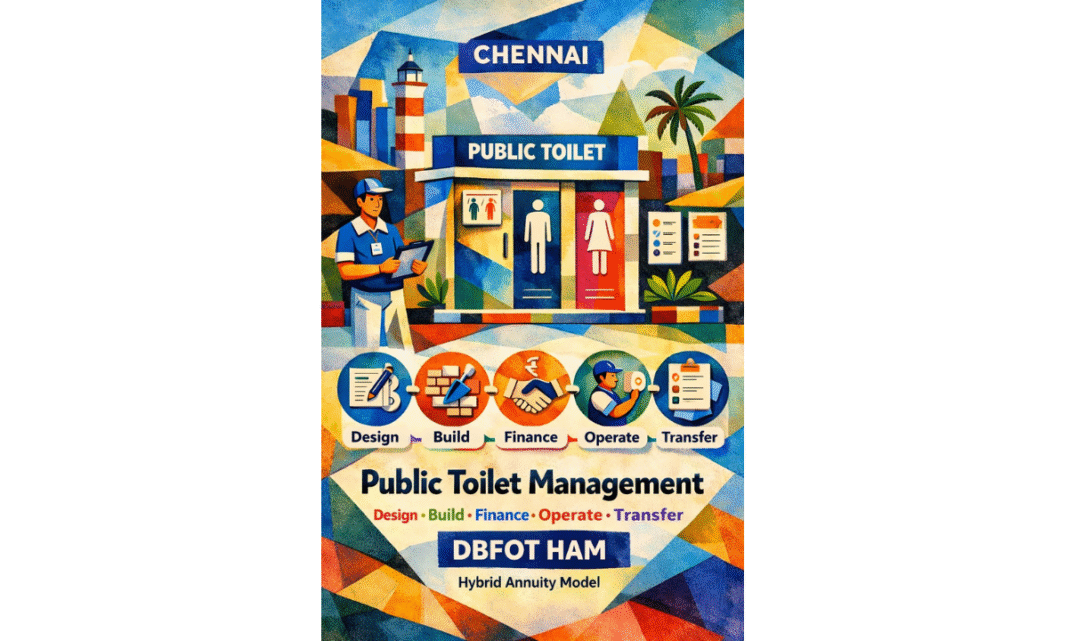

It is here that Chennai’s initiative transcends sanitation and enters the realm of institutional architecture. The Greater Chennai Corporation has anchored its programme in a Design–Build–Finance–Operate–Transfer framework structured under the Hybrid Annuity Model. This is not traditional public works contracting. It is lifecycle governance embedded in contractual design.

Under this arrangement, the private concessionaire is responsible not only for construction but for sustained operation and maintenance. Capital expenditure is partially disbursed during the build phase; the remaining investment is recouped through fixed annuity payments over the concession term. Crucially, those payments are tied to measurable service benchmarks: uptime ratios, cleanliness audits, maintenance compliance, and inspection scores. Completion alone does not trigger revenue. Performance does.

This distinction is decisive. Across India, infrastructure has too often been treated as an event — built, inaugurated, photographed, and gradually neglected. Maintenance budgets shrank; oversight waned. Chennai’s model disrupts that cycle. By binding financial flows to service delivery, it internalises accountability within the contract. Incentives align with sustained quality rather than ceremonial completion.

Such an approach demands administrative capacity. Footfall analytics, ward-level usage patterns, inspection logs, response timelines, and hygiene scorecards become governance instruments. Data, in itself, is not reform. But measurable performance constrains denial. When deficiencies are quantifiable, they become actionable. Transparency recalibrates political incentives.

The ramifications extend beyond sanitation. If Chennai can enforce performance-linked discipline in a sector historically synonymous with neglect, it establishes a replicable governance template. Bus shelters, urban parks, decentralised waste facilities, and parking infrastructure — assets that frequently deteriorate post-inauguration — can be integrated into similar contractual ecosystems. The innovation is not cement or tile. It is institutional maturity.

For Tamil Nadu, the implications resonate nationally. Public toilets are among the most routinely failed civic assets in Indian cities. Ensuring consistent quality over years — not months — requires regulatory vigilance, contractual enforcement, and citizen cooperation. If Chennai sustains standards over the concession period, it signals something larger than sanitation reform. It signals reliability.

Reliability in the mundane redefines public expectation. When a service long associated with dysfunction begins operating predictably, citizens recalibrate what they consider acceptable. Garbage collection, water distribution, street lighting — all are judged against a higher baseline. Rising expectations, far from destabilising governance, can drive systemic improvement.

The trajectory is not predetermined. Oversight could weaken; enforcement could falter. Institutional discipline must be continuously asserted. Technology alone cannot guarantee durability. Administrative continuity, transparent auditing, and civic adherence remain decisive variables.

Yet if Chennai sustains this model, Tamil Nadu will have demonstrated a principle that challenges prevailing narratives of Indian urban reform. Governance transformation need not originate in monumental spectacle. It can begin with the most ordinary civic facility — provided financing is structured intelligently, performance is monitored rigorously, and maintenance is treated as non-negotiable.

The outcomes are tangible. Reduced disease incidence. Expanded mobility for women. Formalised livelihoods for sanitation workers. Strengthened institutional credibility. In shifting the metric of success from construction to sustained service, Chennai is not merely upgrading toilets. It is recalibrating the relationship between citizen and state.

In doing so, Tamil Nadu positions itself not as a participant in India’s urban evolution, but as its pace-setter. Trust, after all, is not forged in megaprojects alone. It is built in the consistent delivery of the everyday. And in that quiet discipline, Chennai is setting the standard.